Despite the title, this post is not about helping software companies commit fraud on their investors. Instead, we analyze some common ways software companies can mislead investors. These can range from “honest” mistakes due to accounting basics not being fully understood to straight-up fraud. Therefore, this post aims to understand some of the nuances that might deceive investors.

Misleading Practices with GAAP

GAAP Accounting

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) provide a standard framework for financial accounting. However, the flexibility within GAAP can be exploited to create a more favorable financial outlook. Here are some common practices:

-

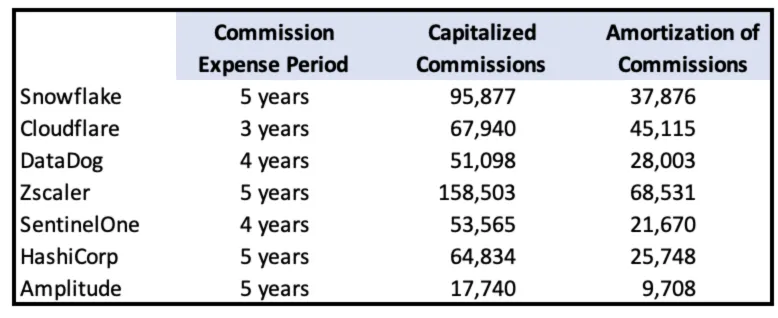

- Capitalization of Sales Commissions

Traditionally, companies expensed sales commissions when they were paid out, impacting the income statement in that period. Under GAAP, companies are allowed to capitalize these costs and amortize them over several years. See some examples from publicly listed companies:

This change can obscure the actual cost of acquiring customers and inflate short-term profitability. Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is typically calculated by summing all sales and marketing (S&M) expenses, including commissions, required to generate new Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR). However, if commissions are not expensed at the time the ARR is obtained, the CAC calculation will not fully reflect the true cost of closing a deal. This discrepancy becomes apparent when growth slows. During slower growth periods, new ARR decreases significantly, but GAAP commissions remain high due to the expensing of previously incurred high commission amounts.

-

- Capitalization of Internal-Use Software

Development costs for net new functionality of a SaaS product, which would typically be expensed as incurred, are often capitalized and amortized over time.

Although there is accounting guidance and standard practices that have developed around how much should be capitalized, it is still a judgmental/grey area. One of my favorite quotes from a Big 4 auditing partner:

“We want you to capitalize something because the rules require it, but we don’t want you capitalizing too much because it’s less conservative (since it delays more expense).”

There are some pros and cons to capitalizing lots of R&D costs.

Pros: Capitalizing internal-use software can improve overall efficiency metrics. Operating Income and EBITDA appear higher during growth phases because these costs are deferred on the balance sheet rather than being expensed immediately. For companies experiencing consistent growth, the deferred costs balance out with new capitalizations, maintaining stable financial metrics.

Con: Amortizing internal-use software impacts gross margins by expensing it through COGS rather than R&D. This can negatively affect gross margins, which are crucial for assessing a company’s long-term profitability. Consequently, CFOs often minimize capitalizing these costs to protect gross margins.

Public software companies typically amortize internal-use software over 3 to 5 years, constituting around 5% of R&D costs. Variations in this practice can significantly impact financial comparisons. For instance, if HashiCorp amortized costs over 2 years like Datadog instead of 5, the financial outcomes would differ materially.

-

- Stock-Based Compensation (SBC)

SBC is a common practice in tech companies, used to incentivize employees without immediate cash outflows. While GAAP requires reporting SBC expenses and it is often looked at as a % of revenue, the real concern is dilution. Companies with falling stock prices might report lower SBC expenses as a percentage of revenue, while the actual dilution effect on shareholders can be significant.

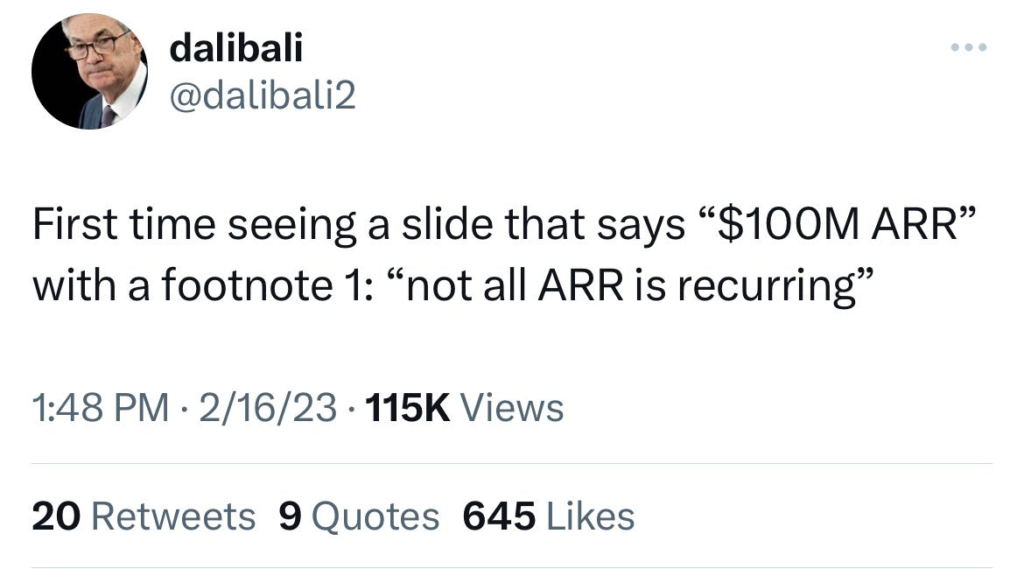

Expense Categorization and Its Impact

GAAP provides guidelines for accounting practices, but not everything is clear-cut. The standards allow for a significant amount of judgment and variation, which can diminish the reliability of certain financial benchmarks, especially for smaller companies. This flexibility means that financial statements can vary widely in how they represent a company’s financial health, making comparisons and assessments more challenging.

Customer Success Costs

How companies categorize customer success costs can greatly affect their financial statements. If these costs are included in the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), they reduce gross margins, but if categorized under Sales and Marketing (S&M), they can inflate perceived efficiency.

For example, including customer success costs in COGS might lower the gross margin from 80% to 75%. However, categorizing them under S&M can keep the gross margin higher, misleading investors about the true cost structure and operational efficiency.

A common way to (over)simplify the issue is to put CS in COGS if they service existing revenue or in S&M if they acquire new revenue.

Recruiting Costs

The categorization of recruiting expenses also varies. Some companies include these in General and Administrative (G&A) expenses, while others might allocate them to different departments. This practice can skew comparisons of efficiency metrics across companies.

For instance, placing recruiting costs in G&A can artificially inflate the perceived efficiency of operational departments like R&D or S&M, as their expenses appear lower compared to companies that allocate recruiting costs directly to these departments.

G&A as a Dumping Ground

Early-stage companies might misuse G&A by allocating various unrelated expenses to this category. This can make other efficiency metrics like R&D or S&M ratios appear more favorable.

A startup might allocate office rent, legal fees, and even some marketing costs to G&A, making their R&D and S&M spending appear leaner. This misclassification can distort an investor’s understanding of where the company is truly spending its money.

Other Financial Manipulation Tactics

Most of these items are exclusive to privately held companies. This is because company management controls the narrative and reporting, and definitions can be loose. Additionally, many investors may not have a deep technical finance background and may not dig very deep on each investment.

-

- Burying the Balance Sheet Detailed balance sheet data often reveal manipulative practices, and often companies only share the income statement and cash flow. This makes it harder for investors to discern financial health accurately. For example, hiding off-balance-sheet liabilities, like certain lease obligations or debt, can mislead investors about the company’s leverage and risk profile.

-

- Efficient Operating Plans Some companies present operating plans that neglect necessary future growth investments, falsely presenting a picture of short-term efficiency. A company might underinvest in crucial areas like marketing or R&D in the current period to show better efficiency metrics. While this might boost short-term performance, it can be detrimental to long-term growth and sustainability.

-

- Aggressive Cash Management Techniques like delaying payments to suppliers or accelerating collections from customers can temporarily improve cash flow metrics. These practices can create a misleading picture of financial health. For instance, a company might delay payments to suppliers at the end of a quarter to show higher cash reserves, giving the illusion of better liquidity. Similarly, offering discounts to customers for early payments can temporarily inflate cash inflows.

-

- Non-Standard Definitions of ARR Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) is a critical metric for SaaS companies, but definitions can vary. Some companies might include one-time fees or use different criteria, misleading investors about the sustainability and growth of their revenue.

A company might define ARR to include not just recurring subscription fees but also one-time setup fees or professional services. This inflates the ARR figure, giving a false impression of stable, recurring revenue streams.

-

- Challenges with Early-Stage Companies Financial statements from early-stage companies can be particularly unreliable due to the lack of strong accounting controls. Without an experienced controller and audited financial statements, it’s difficult to ensure accuracy and transparency. Early-stage companies might inadvertently or deliberately misclassify expenses or inflate certain metrics to appear more attractive to investors. For example, a startup might overstate revenue by recognizing it too early or understate expenses by deferring them. These practices can significantly distort the financial health and operational efficiency of the company.

Conclusion

Investors and operators must develop a keen eye for these financial tactics to avoid being misled. Scrutinizing both income statements and balance sheets, asking detailed questions, and demanding transparency in financial reporting are essential practices. Recognizing these strategies can help investors make more informed decisions and protect themselves from potential financial misrepresentations.